Bernards Blog 17

One of the joys of taking a short lockdown break from level 2 to a more rural setting has prompted me to work on another blog. The opportunity of the journey gave me a chance to consider the extraordinary change in status of one of our most charismatic birds: The Red Kite. These slender-winged raptors have flashes of brick-red on their wings which catch the sunlight as you see them floating serenely over the M25 and the M40 on a trip towards the midlands and the Cotswolds. This is a welcome result of one of the most successful reintroduction projects ever carried out in Britain, in which kites were re-established throughout much of their former range. (pic.)

Once it was as much a London bird as the Ravens in the Tower of London. The streets of Shakespeare’s capital were full of red kites. “The city of Kites and Crows” he called it. Although magnificent in appearance, they were scavengers, never short of a meal at a time when people threw their rubbish in the streets. They also stole washing off lines for their nests, and as Shakespeare writes in A Winter’s Tale, “When the kite builds, look to lesser linen”. But as public hygiene and waste disposal improved, the red kite was robbed of its place in London’s eco-system. By the end of the 18th century it was extinct as a breeding bird, and It was last seen on the streets of the capital in 1859.

Motorways are actually one of the best places to see red kites as they float high over the verges in search of food – dead or alive- to scavenge or kill. They are joined, particularly in the Oxford region of the A40, by recolonising Buzzards where pheasant road casualties are a boon. Today, buzzards are not just our commonest, but also one of our most familiar birds of prey, a reminder that not everything is getting worse for Britain’s wildlife. (pic.)

The strange thing about these magnificent birds is, perhaps, our changing attitude towards them. Not everyone welcomes their return. There have been calls for the licensed killing of buzzards where they take pheasant chicks, even though, as conservationists point out, the buzzards are a native species, while pheasants are artificially bred and released for shooting. Surely these birds have been given a helping hand from us to finally return to the places they should never have left.

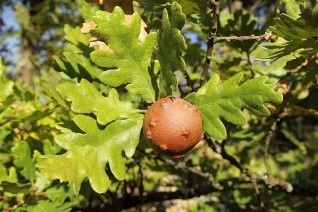

Have you noticed the ‘oak apples’ this year? A stroll through the churchyard or nearby woods this last few weeks has been accompanied by the sound of falling acorns and underfoot there seems to be more than ever being trampled whilst a hard-hat would not be out of place in some areas. These seeds from the oak trees are packed with carbohydrates, protein, fats and minerals that provide nutrition now and through the winter for our native wildlife. Many acorns are buried and stored which is beneficial for the oaks in order to germinate or they will dry out and to ensure that they are not all eaten, oaks and other nut bearing or “mast” trees produce their seeds in cycles. Every few years a “mast year” occurs (possibly 2020) and the habitat is saturated with an abundance of seeds so that predators cannot eat them all.

That was a rambling nothing to do with ‘oak apples’ but you can spot these little round, vaguely apple-like growths or ‘galls’ produced by the oak trees reactions to little wasps that lay their eggs inside the oak bark. They are not dangerous to the tree but are essential to developing oak apple gall wasps and it forms a safe home as well as food for the young wasps.

bm

FOOTNOTE: I wrote this Blog earlier in w/c 26th October and whilst getting it proof-read, put the tv to BBC ‘Autumnwatch’ on Friday 30th. It was pleasing to see they mentioned this year’s oak trees having a “mast” year. Rewarding, but sorry I was not first to bring you the news. B

You must be logged in to post a comment.